The recent Wikileaks farrago, and indeed all leaks in the Internet age, put an end to the idea that governments can and/or should govern by keeping people in the dark.

The philosopher Leo Strauss (1899-1973) was accused by Shadia Dury of teaching that "perpetual deception of the citizens by those in power is critical because they need to be led, and they need strong rulers to tell them what's good for them." This view of Strauss is, not surprisingly, rejected by Straussians, but the suspicion remains that those in government feel that they are in some way special. The other side of this is the common belief that governments know things that common people do not, which gives them a licence to do the insane things that they do (e.g. invade Iraq).

Whatever the truth of Straussian protected knowledge, the fact remains that anyone in government who commits his/her thoughts to paper or electrons must now think twice: How would this look if it surfaced in the public domain?

This is not necessarily a bad thing.

PS Iain Dale is not happy about Assange.

Are there any lengths, he cries, sounding more and more like Indignant of Tunbridge Wells, to which Julian Assange will not go to slag off America and compromise the security of the west?

I pointed out that he did not complain when Wikileaks published the "climategate" papers, which delayed and diluted the response at Copenhagen. Sauce for the goose...

|

|

|---|

Showing posts with label philosophy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label philosophy. Show all posts

Monday, November 29, 2010

Thursday, November 18, 2010

To think, or not to be?

I think, therefore I am.

A reasonable start

for any man,

not just Descartes,

but doesn’t get us far.

“What am I for?”

is more the thought

that calls us to the bar.

Make sure that you don’t fail:

set out to be the alpha male.

get the top job.

Make sure you don’t get stopped

or get your bollocks cropped.

Don’t mention that we’re headed for the shit.

I said it once, I think I got away with it.

Here’s what to do:

Eat, screw,

Look out for number one,

Have loads of fun.

Make mon-

-ey.

Don’t get caught, and if you do

blame it on someone you once knew.

Stay with the pack

head for the brink

and, no matter what may come

just never, ever,

think.

A reasonable start

for any man,

not just Descartes,

but doesn’t get us far.

“What am I for?”

is more the thought

that calls us to the bar.

Make sure that you don’t fail:

set out to be the alpha male.

get the top job.

Make sure you don’t get stopped

or get your bollocks cropped.

Don’t mention that we’re headed for the shit.

I said it once, I think I got away with it.

Here’s what to do:

Eat, screw,

Look out for number one,

Have loads of fun.

Make mon-

-ey.

Don’t get caught, and if you do

blame it on someone you once knew.

Stay with the pack

head for the brink

and, no matter what may come

just never, ever,

think.

© Richard Lawson

Congresbury

3 Sept 2006

Congresbury

3 Sept 2006

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Infinite Monkeys

In Book II, section XXXVII of "De Natura Deorum" Cicero writes;

Is it possible for a man to behold these things, and yet imagine that certain solid and individual bodies move by their natural force and gravitation, and that a world so beautifully adorned was made by their fortuitous discourse? He who believes this may as well believe that if a great quantity of the one-and-twenty letters, composed either of gold or any other matter, were thrown upon the ground, they would fall in such a fashion as legibly to form the Annals of Ennius. I doubt whether fortune could make a single verse of them. How, therefore, can these people assert that the world was made by a fortuitous concourse of atoms, which have no colour, no quality-which the Greeks call 'poiotes', no sense? or there are inummerable worlds, some rising and some perishing, in every moment of time? But if the concourse of atoms can make a world, why not a porch, a temple, a house, a city, which are works of less labour and difficulty?

The beginnings, I think, of the Infinite Monkey theory. :))

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Thoughts on Stoicism

What follows is my contribution to a debate on another network.

Actually, Puck, that is not what Stoic philosophy is about at all. Are you familiar with The Meditations of the divine Marcus Aurelius? If not I would heartily endorse Joe’s recommendation.

Anyway, Stoicism, as represented through books like The Meditations, is simply a way of determining what is important and what is not. It is not about riding oneself to ‘circumstances’, however that is supposed to be defined, and it is certainly not about allowing ‘natural feelings’ to take their place.

I’m not sure exactly what you mean by ‘natural feeling’ anyway, though this would seem to come much closer to Epicureanism. Stoicism is an entirely rational branch of philosophical thought, as opposed to emotive or essential, a way of viewing everything, from ethics to existence itself, through the eye of the mind, in a mood of complete detachment. Moreover, it is not based on fatalism but realism. It’s a kind of standing back, if you prefer, a withdrawing into oneself, as Seneca puts it in the Letters to Lucilius; hence Marcus’ own process of self-reflection.

Yes there is a strong asceticism to the whole doctrine, but it is this that one finds true peace. The process of reflection, or retreat, also allows for continual self-renewal, a washing away of all pain and resentment caused by direct experience. All of the negative experiences of life are, by this scheme of things, based on ignorance or alienation from the higher, and purer, forms of reason.

The practical aspect is also strong. In some ways it is no better basis for dealing with the frustrations, the silliness and the stupidity of every-day life, and of dealing with all of those who embody those negative virtues, particularly the stupid and the ignorant. Anyway, I feel a quotation coming on, and how I love quotations! This is from Book II Part I of "The Meditations":

Begin the morning by saying to thyself, I shall meet with the busy-body, the ungrateful, arrogant, deceitful, envious, unsocial. All these things happen to them by reason of their ignorance of what is good and evil. But I who have seen the nature of the good that it is beautiful, and of the bad that it is ugly, and the nature of him who does wrong, that it is akin to me, not only of the same blood or seed, but that it participates in the same intelligence and the same portion of the divinity, I can neither be injured by any of them, for no one can fix on me what is ugly, nor can I be angry with my kinsman, nor hate him, For we are made for co-operation, like feet, like hands, like eyelids, like the rows of the upper and lower teeth. To act against one another then is contrary to nature; and it is acting against one another to be vexed and to turn away.

Yes, indeed. Ave Imperator. :)

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Wagner the Philosopher

Richard Wagner may have read Schopenhauer but he sure as hell did not understand Schopenhauer! Perhaps apes also read the great pessimist with as little understanding as they bring to Nietzsche?!

Anyway, Wagner, by his own account, read The World as Will and Representation several times, impressed by the idea of music as the striving of the will. But he was equally impressed by the notion of the denial of will. His enthusiasm was expressed in a letter to Franz Liszt: "I have...found a sedative which has finally helped me to sleep at night; it is the sincere and heartfelt yearning for death; total unconsciousness, complete annihilation, the end of all dreams-the only ultimate redemption."

He comes closest to Schopenhauer's ideas in Tristan und Isolde, when the lovers express their longing for their individual existence to end. But Wagner transforms this gloomy abnegation to a climax of erotic love, effectively turning Schopenhauer upside down. Tristan and Isolde do not escape the blind force of Will; they just become yet another link in its ongoing evolution. But, what the hell? The sex was good!

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Moral Transcendence

This is an answer I gave in a debate on the question of moral transcendence.

OK, I’m going to strip this right back, just to uncover some of the assumptions behind my argument that ethics and simple morality are based on transcendent values whereas laws are based on power. I’m not sidestepping your examples, though whether Genghis Khan led a ‘good life’ or a ‘moral life’ is clearly open to question, as, indeed, is that of Ghandi, inasmuch as he pursued political goals which, albeit unintended, had seriously adverse consequences.

Please note I said that ethics were transcendent, meaning they go beyond history and circumstances, not that they were based on a ‘higher law’, which is something quite different. Also there are values that are shared across cultures and traditions; all of the main religions, from Judaism to Buddhism, contain certain core principles governing inter-personal conduct.

Yes, there are societies where killing may indeed have been perceived as a virtue, just as there were societies where cannibalism and head-hunting were also ‘virtuous’, if that word has any meaning in this context. Let me make it clear that ethics, in the complex philosophical sense, and morality, in the simple sense of knowing right from wrong, are not ‘there’, so to speak, floating around; nor are they God-given. They emerge by a process of deduction and reason, beginning with the ancient Greeks. Socrates is speaking not just to Athenians; he is speaking to all people.

I cannot possibly explore all of the nuances of moral philosophy here; it would just be too horribly complex. Let me just say that my argument is based upon what is known as ‘moral universalism’; that the same principles apply across culture. In simple terms this is based on forms of self-reflection and understanding. On an intuitive level one is aware of the possibility of pain and suffering, and the need to avoid the things that cause pain and suffering, as an act of self-preservation. On a rational level this leads, on the basis of a good life, an awareness that others are also subject to pain and suffering, and the moral position is to avoid inflicting on them what one would wish to avoid having inflicted on oneself. Self-interest and reason coalesce into what I have alluded to as a transcendent value.

For instance Immanuel Kant, one of the architects of the argument I am advancing here, says that moral values-though ‘law’ is his preferred term-are binding on all, irrespective of their empirical circumstances or their individual preferences or proclivities. It is in the exercise of rationality that true moral thought lies. If this did not exist then the only basis for action would be immediate and sensuous impulses, and the only basis for morality one of self-gratification. That is to say, morality enables us to act in defiance of baser impulses, to reject the pursuit of power and glory as a justifiable end in itself, no matter what the consequences, as in the example of Genghis Khan. Morality is a free construct, freely arrived at; not dictated by God or any external impulse. Even Schopenhauer, who argues that Egoism is the guiding principle in all moral choice is forced to admit compassion as one of the ‘mysteries’, as he puts it, of ethics. Compassion reaches beyond egoism; compassion transcends egoism.

Look, I’m going to stop now, though there is so much more I could say. I do not want to test your patience too much, nor do I wish to develop a full-blown dissertation on the philosophy of ethics. Let me just say, returning to my earlier points, that it is possible to recognise the difference between what is moral and what is legal. If I had lived in Nazi Germany I know that my rational understanding, my ability to go beyond the immediacy of my circumstances, would have enabled me to see that the Nuremberg Laws were wrong and un-ethical. If I am a free, intellectually free and rational, then I will not be blinded by sophistry. Law is based on power; morality is based on truth.

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Kant and Religion

The important text here is Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone, published in 1793, in which Kant takes up some of the themes touched on in the three Critiques. He concludes that Christian worship is no more important than any other form of religious belief;

Whether the hypocrite makes his legalistic visit to a church or a pilgrimage to the shrines of Loretto or Palestine, whether he brings his prayer formulas to the heavenly authorities by his lips or, like the Tibetan...does it by a prayer wheel, or whatever kind of surrogate for the moral service of God it may be, it is all worth just the same.

In other words the servile worship of God is no substitute, in Kant's mind, for the transcendental critique. The corollary is that morality does not need religion for its own service, "...but in virtue in pure practical Reason it is sufficient unto itself."

He also takes the Biblical figure of Job as a kind of forerunner of the Enlightenment, a man who speaks the way he thinks, caring nothing for false flattery. In the 1791 On the Failure of All Philosophical Attempts at Theodicy, Kant says that Job "...would most probably have experienced a nasty fate at the hands of any tribunal of dogmatic theologians, a synod, an inquisition, a pack of reverends, or any conspiracy of our day."

I Bring you the Superman...or the Superwoman!

Zarathustra, however, looked at the people and wondered. Then he

spake thus:

Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman- a

rope over an abyss.

A dangerous crossing, a dangerous wayfaring, a dangerous

looking-back, a dangerous trembling and halting.

What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal: what

is lovable in man is that he is an over-going and a down-going.

I love those that know not how to live except as down-goers, for

they are the over-goers.

I love the great despisers, because they are the great adorers,

and arrows of longing for the other shore.

I love those who do not first seek a reason beyond the stars for

going down and being sacrifices, but sacrifice themselves to the

earth, that the earth of the Superman may hereafter arrive.

I love him who liveth in order to know, and seeketh to know in order

that the Superman may hereafter live. Thus seeketh he his own

down-going.

I love him who laboureth and inventeth, that he may build the

house for the Superman, and prepare for him earth, animal, and

plant: for thus seeketh he his own down-going.

I love him who loveth his virtue: for virtue is the will to

down-going, and an arrow of longing.

I love him who reserveth no share of spirit for himself, but wanteth

to be wholly the spirit of his virtue: thus walketh he as spirit

over the bridge.

I love him who maketh his virtue his inclination and destiny:

thus, for the sake of his virtue, he is willing to live on, or live no

more.

I love him who desireth not too many virtues. One virtue is more

of a virtue than two, because it is more of a knot for one's destiny

to cling to.

I love him whose soul is lavish, who wanteth no thanks and doth

not give back: for he always bestoweth, and desireth not to keep for

himself.

I love him who is ashamed when the dice fall in his favour, and

who then asketh: "Am I a dishonest player?"- for he is willing to

succumb.

I love him who scattereth golden words in advance of his deeds,

and always doeth more than he promiseth: for he seeketh his own

down-going.

I love him who justifieth the future ones, and redeemeth the past

ones: for he is willing to succumb through the present ones.

I love him who chasteneth his God, because he loveth his God: for he

must succumb through the wrath of his God.

I love him whose soul is deep even in the wounding, and may

succumb through a small matter: thus goeth he willingly over the

bridge.

I love him whose soul is so overfull that he forgetteth himself, and

all things are in him: thus all things become his down-going.

I love him who is of a free spirit and a free heart: thus is his

head only the bowels of his heart; his heart, however, causeth his

down-going.

I love all who are like heavy drops falling one by one out of the

dark cloud that lowereth over man: they herald the coming of the

lightning, and succumb as heralds.

Lo, I am a herald of the lightning, and a heavy drop out of the

cloud: the lightning, however, is the Superman.

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

An Evergreen Myth

Oh, yes, of course Atlantis exists; you will find it to the north of Utopia and to the east of Erewhon! Yes, it exists; it existed in the imagination of Plato, just as the latter two places existed in the imagination of Sir Thomas Moore and Samuel Butler.

There is nothing, no mention of Atlantis whatsoever, in the literary or historical record prior to the composition of Plato’s dialogues Timaeus and the unfinished Critias. Quite simply it is Plato’s Utopia, set up as a mirror to contemporary Greece . It fell in the end, Plato concluded, because of its impiety, a warning to his fellow countrymen. It was, in other words, simply a dialectical device, one the author used to illustrate and develop his political theories.

So, that’s it. There is no archaeological evidence, no chronicles, no remains, no coins; absolutely nothing. The only dispute amongst serious scholars is the extent to which Plato based his literary invention on older stories or some specific historical event, possibly the eruption of Santorini in the Cyclades Islands in 1500BC, which caused widespread devastation in the Aegean region, and is thought to have led to the beginning of the end of the Minoan civilization on Crete.

The idea was taken up, of course, by those who followed Plato, often only to be parodied and dismissed, beginning with Theopompus, who invented Meropis, his own fantastic world beneath the ocean. The current obsession probably dates no further back than the publication in the seventeenth century of The New Atlantis by Sir Francis Bacon.

And so it went on. Those who believe in Plato’s fiction are in the company of Heinrich Himmler, Alfred Rosenberg, the chief Nazi ideologue, and other such inspired mystics!

But, hey-what the hell?-when a myth is up and running it is impossible to knock down. :-))

Wednesday, July 1, 2009

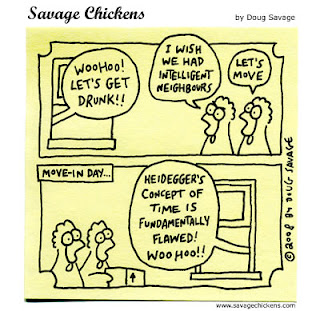

Heidegger and Language

Language was one of Martin Heidegger's central preoccupations. In A Dialogue on Language he wrote "Language is the house of being. Man dwells in this house...In language there occurs the revelation of beings...In the power of language man becomes the witness of Being." Being or Dasein-the central concept in his ontology-is revealed through language.

He also spends time discussing the vacuity of ever-day language, where words lose meaning through overuse. One only has to consider here the use of 'love' in relation to all kinds of experience and tastes, so much so that the original intensity of meaning has been sucked dry. Heidegger says that the key to self-understand is to rediscover the original link between the word and the experience, when, as he puts it, 'Being first spoke' in words like 'peace', 'love', 'truth' and 'compassion'.

It is in the area of the Language of Being, in Heidegger’s own philosophical vocabulary, that his thinking tends to become particularly opaque. His use of all sorts of obsolete and compound expressions makes the English translation of his work problematic, particularly that which he wrote after Being and Time. It's only for the most determined of Beings in the world! :-))

Friday, June 26, 2009

Beans Lead to Hell!

I bet you didn’t know that! Well, they do, or at least they do according to Pythagoras, who wrote, “Eating beans is a crime equal to eating the heads of one’s parents.”

The bean-hating mathematician and philosopher was also a religious dissenter who established his own sectarian colony. Some of the notions put forward concerning diet were eccentric, to say the very least. Pythagoras believed in the transmigration of souls, which could pass from people to animals. So, animal sacrifice was out. Heated spices and herbs were altogether more suitable offering to the gods.

Yes, just as spices were the route to heaven beans took one in the opposite direction. Broad beans, were, so he said, the ladders for the souls migrating from the underworld. Beans grown in a closed pot resulted in a mass of obscene shapes, resembling sexual organs or aborted foetuses. I know it sounds just so funny but for Pythagoras and his followers diet was an important branch of ethics. Well, perhaps it is. :-))

Monday, June 22, 2009

Being and Nothingness as Political Commentry

Envisage, if you can, Paris in 1943: a bleak place, one where the arena of personal freedom was growing more circumscribed by the day. In the streets, alongside the German occupiers, there were French Fascist auxiliaries of one kind or another, with links to Marcel Déat and others among the so-called Paris Collaborators. The previous year all French Jews had been required to wear the yellow star, not by order of the Germans, but on the initiative of Darquier de Pellepoix, Vichy's Commissioner for Jewish Affairs. Round-ups and deportations were now a regular occurrence. Through the city German propaganda, evoking final victory, was an ever-present feature of life in public places. Denunciations, anonymous letters and police raids wee a constant threat. France has been seized by a Judeo-Bolshevik phobia. The atmosphere is stifling.

So, for Sartre, and every other Frenchman, objective freedom has all but gone. It is against this background that Being and Nothingness, was published, a profoundly Cartesian work, one where subjective forms of freedom find their greatest defence.

There, in subjective consciousness, lies the origin of one's absolute freedom, one that is shaped in a state of permanent criticism. All labels are rejected-"How them shall I experience the objective limits of my being: Jew, Aryan, ugly, handsome, kind, a civil servant, untouchable, etc.-when will speech have informed me as to which of these are my limits?" It is from these labels that alienation and inauthenticity are created: "Here I am-Jew or Aryan, handsome or ugly, one armed etc. All this for the Other with no hope of apprehending this meaning which I have outside and still, more important, with no hope of changing it...in a more general way the encounter with a prohibition in my path ('No Jews allowed here')...can only have meaning only on and through the foundations of my free choice. In fact according to the free possibilities which I choose, I can disobey the prohibition, pay no attention to it, or, on the contrary, confer upon it a coercive value which it can hold only because of the weight I attach to it."

Sartre's theory of freedom is expressed, for the most part, in highly abstract terms, but it still has to be read against a specific historical background. The call for freedom, and the parallel denunciation of all forms of bad-faith, was never more meaningful in Nazi France.

Why did the Germans allow this? Well, because they operated in some areas a fairly relaxed censorship policy, especially over such abstract works as Being and Nothingness. It also helped if the author expressed an anti-German message which the Germans themselves could not understand, as Sartre did in his play, No Exit, which concludes with his most famous quote "Hell is other People", or l'enfer, c'est les autres in French. By this time the French ad long ceased to refer to the occupiers as Boches-they were, quite simply, Les autres

Tuesday, June 16, 2009

More Thoughts on Machiavelli

I'm considering one reasonably well-known statement from Chapter Six of The Prince: "Hence it is that all armed prophets have conquered, and the unarmed ones have been destroyed." For Machiavelli this is the central lesson of history. But it is also a message that goes against that of the church: for the 'unarmed prophet' is Christ. The 'prophet armed' is, of course, Mohammed.

However, I do not think that 'Old Nick' was delivering am anti-Christian message as such. After all, for centuries the Christians had taken up arms, in wars both just and unjust. Machiavelli’s great crime was, as I have said, to describe the practice of politics, free from ethical and theological fictions: for it was right, as he puts it, "to represent things as they are in real truth, rather than as they are imagined."

In essence, therefore, the message was a practical one; that in a world of deceit and treachery that those who seek to act virtuously in every way-to follow pure Christian doctrine, if you like-are on the road to self-destruction, not self-preservation. If the Prince is to maintain his rule he must learn "how not to be virtuous and make use of it according to need." Christ was shown the kingdoms of the world and rejected them. For the Prince Machiavelli repeats Satan's temptation, urging him to take up the sword for the sake of the good that can only be accomplished by the possession of power.

Machiavelli intended his brilliant little treatise both as a satire and an analysis of how attain power and, more important, how to hold it. In the treacherous world of sixteenth-century Italian realpolitik there is simply nothing to be gained from the exercise of virtue for the sake of virtue. The exhortations of his Humanist contemporaries, notably Thomas More and Erasmus, the Christian ethics they advance, were no more than a comforting illusion. It's acutely ironic that the Church, for all its disapproval, advanced men like Pope Julius II, for whom The Prince might very well have served as a personal manifesto

Thursday, June 11, 2009

Existentialism and Fascism: the Case of Jean Paul Sartre

Sartre's understanding of politics was not just dangerous, it was dangerously incoherent! He simply could never make up his mind over which direction he wished to travel. I think he saw in politics a way of seeking confirmation of himself, a classic example of existential bad-faith! On Fascism itself we have the words that de Beauvoir gave to a resistance leader "...if Fascism were to triumph, that's just what would happen. There would be no more human beings..."

In other words there can be no human beings in the total absence of freedom, understanding humanity as a fluid rather than a static concept. But this statement is just as valid in relation to Communism, not as it existed as a theory, in the minds of the likes of de Beauvoir and Sartre, but as a living practice. On Fascism there is also the observation in Existentialism is a Humanism that if the doctrine prevailed "Fascism will then be the human realty, so much the worse for us." It didn't seem to stop the master publishing in occupied France, though!

Tuesday, June 9, 2009

Wittgenstein the Mystic

In the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus Wittgenstein says that the limits of thought are determined by the limits of language. In other words, we cannot go beyond language; for to do so would be to go beyond the limits of logical possibility. Logical propositions, expressed in language, are, according to Wittgenstein, 'pictures of the world.' This means, in effect, that certain things simply cannot be said if they do not correspond to the reality of the world; this means that the Tractatus itself cannot be said; for the various propositions are not pictures of the world!

Wittgenstein, recognising this problem, tried to overcome it by saying that although certain things cannot be said to be true, they can be shown to be true, although he eventually slams the door behind him in his concluding proposition-‘Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must be silent.' Consider the example of God. Wittgenstein says He exists, but He falls into the category of things that cannot be thought about or spoken. So the Tractatus remains, though this is not always fully understood, a blend of logic and mysticism; yes, mysticism.

The objections to the Tractatus go even deeper than that. How do we know that the relation between language and reality is a 'logical form'? Wittgenstein offers no solution to this problem. More than that, the category of things we are not, by his methodology, supposed to talk about, we simply must talk about, if social existence, civilization itself, is to be possible. For instance, we are not supposed to talk about good and evil, or even more basic concepts of right and wrong. Art also falls into the category of the inexpressible, which means that all forms of aesthetic language are simply nonsense.

In the end the Tractatus might be said to be both brilliant...and arrogant. The author himself eventually exploded the boundaries he had imposed on thought and action.

Wittgenstein at Cambridge

There are still stories circulating in Cambridge about Wittgenstein's time. There was a bizarre, almost Monty Python-like quality to his lectures. His students were obliged to bring along deck-chairs, on which they all sat in absolute silence while the professor remained immersed in thought. Every so often this silence would be punctuated as Wittgenstein, in the midst of deep labours, would deliver some idea! He would on occasions turn on one of his students and start a rigorous intellectual interrogation, a process that has been likened to being under examination by the Spanish Inquisition.

He had the capacity, by sheer strength of his intellect, and his relentlessness in pursuit of a point, to reduce his audience to a state of terror. The only person with sufficient courage to stand up to him was Alan Turing. Wittgenstein maintained in one of his lectures that a system-such as logic or mathematics-could remain valid even if it contained a contradiction. Turing rejected this, saying there was no point in building a bridge with mathematics that contained a hidden contradiction, otherwise the structure might collapse. Wittgenstein responded by saying that such empirical considerations had no place in logic, but Turing persisted. How I would love to have been present!

Wednesday, June 3, 2009

I Think Therefore I Am; or I Think I Think I Am!

I read this in Descartes' "Meditations on First Philosophy";

Next I examined attentively what I was. I saw that while I could pretend that I had no body and that there was no world and no place for me to be in, I could not for all that pretend that I did not exist. I saw on the contrary that from the mere fact that I thought of doubting the truth of other things, it followed quite evidently and certainly that I existed; whereas if I had merely ceased thinking, even if everything else I had ever imagined had been true, I should have no reason to believe that I existed. From this I knew that I was a substance whose whole nature is simply to think, and which does not require any place or depend on any material thing, in order to exist. Accordingly this I-that is, the soul by which I am what I am-is entirely distinct from the body, and indeed is easier to know than the body, and would not fail to be whatever it is even if the body did not exist.

In the end Descartes 'resolves' the whole problem of the mind-matter interaction by an act, it might be thought, of intellectual bad-faith; by saying that it is a mystery, only understandable to God.

Picture, if you will, the following images. There is a bewigged philosopher in a pensive mood. A bubble appears from his mind with a question mark. “Ah”, says the sage, “I think therefore I am.” The said philosopher continues in his pensive mood. Another bubble appears. This time nothing comes. A look of panic appears on the thinker’s face. The bubble only contains an exclamation mark. And then-POOF!-the thinker vanishes from the scene, wig and all! :))

Next I examined attentively what I was. I saw that while I could pretend that I had no body and that there was no world and no place for me to be in, I could not for all that pretend that I did not exist. I saw on the contrary that from the mere fact that I thought of doubting the truth of other things, it followed quite evidently and certainly that I existed; whereas if I had merely ceased thinking, even if everything else I had ever imagined had been true, I should have no reason to believe that I existed. From this I knew that I was a substance whose whole nature is simply to think, and which does not require any place or depend on any material thing, in order to exist. Accordingly this I-that is, the soul by which I am what I am-is entirely distinct from the body, and indeed is easier to know than the body, and would not fail to be whatever it is even if the body did not exist.

In the end Descartes 'resolves' the whole problem of the mind-matter interaction by an act, it might be thought, of intellectual bad-faith; by saying that it is a mystery, only understandable to God.

Picture, if you will, the following images. There is a bewigged philosopher in a pensive mood. A bubble appears from his mind with a question mark. “Ah”, says the sage, “I think therefore I am.” The said philosopher continues in his pensive mood. Another bubble appears. This time nothing comes. A look of panic appears on the thinker’s face. The bubble only contains an exclamation mark. And then-POOF!-the thinker vanishes from the scene, wig and all! :))

Time as Experience

Henry Bergson's seminal Time and Free Will distinguishes scientific knowledge of ourselves from our own experience of ourselves. The division here is between time as a spatial concept, a succession of separate and distinct events, and time as a living experience, a flow or a stream, uniting the present with the past and the future. According to Bergson, this flow resists any kind of measurement. The notion of 'time experience' was to be highly influential, used by Marcel Proust, among others, in À la recherché du temps perdu.

In his work on phenomenology, Edmund Husserl deepened Bergson's work by analysing exactly how time appeared in consciousness. Under the influence of both Bergson and Husserl, in 1927 Martin Heidegger advanced the notion that Dasein-subjective existence-has its being in all three temporalities; its past, its present and its possible futures.

Death and Dilemma

This is an answer I gave to a question centering on certain moral dilemmas.

But you already know my views on the first dimension of your question-or dilemma-so no need to travel again down beaten paths. I will just add one small caveat. For me it’s not a question of being pro-life or pro-choice. When it comes to questions of pregnancy and abortion I do not take an abstract position. I know what I would do in the circumstances I alluded to in our past discussion. I will not be dictated to, and I will not dictate to others.

The second element is pitched, I think, more at your fellow Americans, or to people that still live under a system of justice where death is the ultimate penalty. We haven’t had the death penalty in England for almost fifty years now, and I simply cannot envisage it ever returning. To me it seems positively barbaric, no matter the method. Albert Pierrepoint, the last official hangman in England, wrote an autobiography, in which he said that the death penalty was not about justice; it was about vengeance. These are his exact words;

I have come to the conclusion that executions solve nothing, and are only an antiquated relic of a primitive desire for revenge which takes the easy way and hands over the responsibility for revenge to other people...The trouble with the death penalty has always been that nobody wanted it for everybody, but everybody differed about who should get off.

Now, I do not want to misjudge you but you seem comfortable with the notion of vengeance. I am not, because I feel that it uncovers even baser emotions. But I’m talking in the abstract, am I not? That’s the very thing I said I would not do over the issue of abortion. I can’t honestly say how I would feel if someone close to me was the victim of some awful crime. I may very reach deep into notions of revenge, of a need for satisfaction in revenge.

But I note that one of your respondents has taken that final step, arguing even for drawing and quartering, even using the vilest of imagery to express her enthusiasm. I suppose it might even be a spectator sport, in the same fashion as the Middle Ages; to watch a man hung and then cut down still choking; to then have his penis and testicles cut off, his chest opened and his bowels removed, all this while alive and screaming-screams that would echo in one’s mind for as long as one was alive-, with the executioner, covered in blood, right up to his elbows, looking like a butcher. Women avoided this: they were simply burned alive. In killing monsters are we to become monsters? One Hannibal is destroyed; a dozen more arise in his shadows. Yes, it’s true: if you stare into the abyss long enough the abyss stares back into you.

As far as thinning out the herd is concerned, yes, there are some people I think should never have been placed upon this planet, but I’m mindful of the words of the Ghost of Christmas Present to Scrooge;

If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future, none other of my race,” returned the Ghost,”will find him here. What then. If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Scrooge hung his head to hear his own words quoted by the Spirit, and was overcome with penitence and grief. “Man,” said the Ghost,”if man you be in heart, not adamant, forbear that wicked cant until you have discovered What the surplus is, and Where it is. Will you decide what men shall live, what men shall die. It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man's child. Oh God. to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust.

Can I pose a moral dilemma for you? It’s a bit of a trap, fashioned around your personal convictions, so please avoid it if you wish. Anyway, I’m going to give you a time-machine, to take you back to Europe over a hundred and twenty years ago, to Austria, to be precise.

It’s the autumn of 1888. Twenty-eight year old Klara Pölzl is pregnant. She is delighted; this will be her fourth and, although she does not yet know it, the baby is a boy. Yes, she is delighted…and she is afraid; for, you see, she lost her previous children-two boys and a girl-in infancy. This little one, who is destined to survive, will be truly special, given all the love and devotion of which Klara is capable.

Now, your task is to persuade Klara-force her, perhaps- to have an abortion. Why? What reason would you have for so wicked an act? Well, you see, Pölzl is Klara’s maiden name: her married name is Hitler. You have the power to save millions of lives, the lives of so many children not yet born and not yet conceived; children who might very well have grown to be great people, to have discovered a cure for one or other of the dreadful diseases that still haunt the human race, or to be a great writers or artists. Could you do it; would you do it?

Friday, May 22, 2009

God is Dead

I read again the story of the hermit in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. His life is based upon God's presence. Every action he performs is in praise of the deity. If God is dead then the hermit is dancing in a void, under the illusion that he has an audience. The saint, it might be said, has lost his witness, the only thing that hitherto gave life meaning. But it is far more significant than that; for when God died "...sinners died with him." They died as sinners because their acts no longer conferred any such identity.

Let me put this another way: with the death of God the world has lost its moral centre, the pole from which all meaning was derived. There are no more Saints just as there are no more Sinners. There are only questions, always questions. For Karl Jaspers, taking up Nietzsche's baton, the death of God is a historical situation through which humanity must pass on towards new forms of meaning. Nobody can escape the death of God, atheist or believer. And therein lies the most delicious of ironies!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)